High LAND/FEARANN: How We See Our Highland Landscapes

LONG READ: The text below is a transcript of a talk given at the High LAND/FEARANN event in Abriachan in June 2018

Land Question/Ceist An Fhearainn

The following overview is a very broad brush introduction to some of the themes we hope to explore as part of the Fearann / Land project, including cultural perceptions of the land in the Highlands. The wider argument is that the movement for land reform cannot be seen in isolation, but as part of a wider cultural process.

We’re talking about the Land Question/Ceist An Fhearainn in a largely rural Highland context, but it is important to note that this is a live issue in urban contexts too. This Land Question is related to policy areas of Environment, Crofting, Hill Farming, Forestry, Community Empowerment, Health & Wellbeing, Equality & Rights, Economic Development, Tourism, Education, Transport, Gaelic Language, Culture & Heritage, and more - all nicely put it boxes. But life is not lived in boxes. At state level, we need radical reform. At the grassroots, we need active citizens. The story of the land involves us all: it is what we share in common. Our ability – collectively or as individuals – to enact any kind of political change is intimately tied to our ability to make sense - to make meaning - of the world around us. We can all play a part.

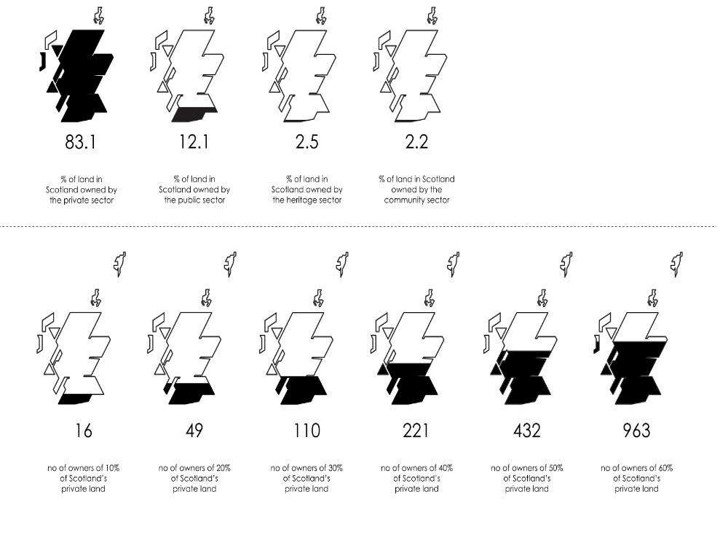

Driving the wider movement for land reform, both locally and globally, is the desire to tackle injustice, both historical and contemporary - ecological, cultural and political. Many contemporary injustices arise from historical injustices, and this includes - perhaps most explicitly - the inherited patterns of land ownership. In the Highlands, land ownership is the most inequitable in Europe. Thanks to Calum MacLeod, policy director at Community Land Scotland, for sharing this slide – based on research done by Andy Wightman - to illustrate this point.

You would be forgiven for thinking that the Highlands has two parallel universes. There is the Highlands where we live and work and where our communities play out, and there is the playground for the super-rich to indulge in the Romantic imagination - in deer stalking and grouse shooting - activities which are devastating for the environment. The following quotes, encapsulate sharp end of land injustice:

“For most buyers, an estate is a luxury purchase to enjoy, not unlike a superyacht or a Lamborghini...

In contrast, communities buy estates to help safeguard their own futures.’”

— Calum MacLeod, Scotsman article 2018

“There are thousands among Europe’s party elite who believe that Scotland truly is an under-populated wilderness where you shoot your dinner by day and dance on your tiptoes by night alongside men with skirts and maidens with marble bosoms. ”

— Kevin McKenna, Scotland has the most inequitable land ownership in the west. Why? (2013)

Activism

When most people think of ‘activism,’ they imagine people chained to trees and buildings, shouting slogans at protest marches or angrily complaining. Activism can be that, but it is much more than that. In many ways, activism is simply the practice of participatory democracy, of active citizenship: of getting stuck in and not waiting to be led. Activism enables us to participate directly and creatively in culture and in a democratic process (a process that is often otherwise marginalised to ticking a box). Activism can challenge the inevitability of injustice and gives people hope that change is still possible. Activism helps us see things differently. It opens up opportunities and possibilities for individuals and groups to connect, organise and make things happen: to change things. Once connections are made, this leads to new ideas being created, bringing about a change in everyone involved. Chris Erskine writes that it this a simple process: of connection, creation, change.

Our generation faces huge problems ahead: ecological and climate crises, global capitalism and its environmental destruction; challenges to globalisation with the rise of right wing populism and the retreat into entrenched ethnicities. Brexit. Trump. In the Highlands we see depopulation, environmental degradation, housing crises, demographic shifts.

‘The great disease of our time,’ writes Alastair McIntosh, 'is meaninglessless':

“If fresh wellsprings of hope are to be found, we must first cut through the collective hallucination that ‘there is no alternative’ to nihilism. We must dig where we stand. We must get beneath the grassroots of popular culture and down to the eternal taproot. Here new life can grow from ancient stock.”

— Alastair McIntosh, Soil and Soul: People v Corporate Power (2001)

I want to pick up on this idea of 'digging where we stand.' This metaphor takes in our own personal roots and background, our history and culture as well as the literal ground beneath our feet. The idea is that by researching and learning about our own history and the place where we are living, we - as individuals and as groups - can regain some control over the understanding of our lives and our inter-connectedness. The idea here is that memories make dreaming the future possible.

Inspired by philosopher and educator Paulo Freire and his 'conscientisation' method of education in South America, McIntosh talks about the four vital stages in the process of working towards community ownership. These are, he writes:

1) Re-membering: in which we remember the stories of our places. To quote Raghnaid Sandiland’s wonderful phrase, what is needed is a form of 'cultural darning and mending.' Asking searching questions and seeing with new eyes.

2) Re-visioning: envision what our communities could become, sorting the realistic from the fantastic, and asking what kind of people we want to be (and how we want to be remembered).

3) Re-claiming: in which the community makes a claim of right over that which is required for the common good.

The final stage in this process is the ‘strengthening local democratic processes.’ Put another way, it’s the stage of learning (or re-learning) what it really means to be a community.

If anything like a real turning of the times is possible, we need to find ways to re-connect with meaning, to re-connect with the land. There are lots of ways we can do this - through culture, music, language and history; through place-based education and consciousness raising; through spending time in the nature and the outdoors - walking, hiking, biking, hutting, growing, gardening. I’m sure we could come up with a huge list. This re-connection is a vital step to building community confidence.

Radical Roots

We first need to ask, why is the Highlands the way it is?

The story of contemporary land injustice in the Highlands goes back to 18th century, a story which you all know. This said, this is a story that wasn’t always taught in our education system. How many of you learned about this in school?

Following Culloden and the destruction of the old clan system, a new breed of commercially-minded landowners came in and claimed the land. In the old system, the power and status of clan chiefs derived from the number of fighting men at their command, which sustained and nurtured population. People, of course, were not profitable, and so in the new system, they were cleared from the land. The Highland Clearances - Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal - emptied vast swathes of northern Scotland and replaced its settled communities first with sheep, and then with deer. The consequence of this process was huge cultural loss. It is important to say that it is not as simple as non-Gael clearing Gael, but rather a much more complex history; often, the clan chiefs became the aristocracy. It is important not to forget too that this history of violent displacement is linked to coloniality elsewhere; many who travelled to the ’New World’ reproduced this violence that was meted out to them under the protection of the British Empire. Gaels had few options other than to remain oppressed at home, or to emigrate and become entangled in the oppression of others. The ‘oppressed became the oppressors,’ as the saying goes.

Below is an image from Dunmaglass on south Loch Ness, an area of clearance (the location is the same in both images). The cairn as an icon embeds dominant cultural narratives of defeat and exile in the Scottish landscape, associated with loss, with pain, social fracture, displacement and a sense of belonging lost. And here is the other icon: the Duke of Sutherland on Ben Bhraggie hill, near Golspie. Sutherland, of course, was one of the most heavily cleared of the Highland regions.

First 2 images above thanks to Raghnaid Sandilands. Read more: 'STONES AND STORIES: THE DUNMAGLASS CAIRN'

For those left behind in Scotland, there was overcrowding in crofting townships, which were largely on the coast (and where tenants supplied cheap labour for the kelping industries). Poverty and famine was endemic. By the 1880s, discontent gave rise to riots, rent strikes and land seizures, which in turn led to the emergence of the Highland Land League. Names such John Murdoch (1818 - 1903) - who ran the radical ‘The Highlander’ newspaper published in Inverness between 1873 and 1882 - and Màiri Mhòr nan Òran (1824 – 1828) - a songwriter and land rights activist from Skye - should be known to our generation. During the 'Crofters Wars,' most famously the 'Battle of the Braes' near Portree, Skye in 1882 - when crofters refused to pay their rents to Lord MacDonald - it was the women who instigated an attack on the retreating police force. They had no weapons, only sticks and stones. Following this, Royal Navy gunboats were sent in to meet further unrest in Glendale. The publicity that followed led to the Government-led Napier Commission, and then to the Crofters Act of 1886, which granted crofters security of tenure. This was a watershed moment that shaped subsequent land reform as we know it today.

Land action continued into 20th century, with post WW1 raids in Vatersay on Barra, Coll and Gress on Lewis, and Knoydart. You can see the chronology of events on this timeline. There are many excellent books on the subject. I would recommend the work of historian James Hunter. A great source of information on this topic is the book As an Fhearann - From the Land. Clearance, Conflict and Crofting: A Century of Images of the Scottish Highlands (1986), edited by Malcolm MacLean.

Landscapes of the Imagination

These material and cultural issues were further complicated by the commercial success of invented traditions, which have continued to distort and obscure Gaelic history and culture into the present day; particularly, perhaps our visual culture, and how we see the Highland landscape. Throughout the centuries, Romantic representations of the Highlands have provided not only a psychological escape from contemporary reality, but also an escape from the history of the Highlands itself.

The interplay between ‘fiction’ and ‘history’ is quite fascinating when we reflect upon how we ‘see’ our landscapes here in the Highlands, both from within and from outside. Looking at dominant visual stereotypes (often seen in tourist literature - more of this later), the Highlands is a dreamlike place that belongs to the past, where the people are dead and gone, disappearing into the mists of time. The glaring question, when looking at this imagery, is: where are all the people?

The point here is that the land-scapes of human experience are not just perceived; they are also imagined. David Lowenthal, a heritage and landscape scholar, talks about the concept of ‘ landscape’ encompassing both the ‘world outside’ and the ‘pictures inside our heads.’ What he is getting at here is not pictures inside our heads in the narrow sense of graphic scenes and maps, but as world pictures: ontological cosmologies that shape who we are, how we think, and how we live, ways of being. We project aesthetic values and narratives, real or imagined, onto the landscape, ascribing meaning to its features. The expression of landscape, therefore, is very much cultural process; a process by which identities are formed. Crucially, like our own identity, these expressions can change.

Perceptions of the Highland landscape have largely been shaped - mythologiesd - by the European Romantic imagination (and the associated aesthetic ideals of the sublime and the picturesque.) This was not always the case. It is quite remarkable that the dramatic topography of the Highlands, derided by Samuel Johnson in 1773 as a ‘wide extent of hopeless sterility’, could be seen, less than thirty years later by John Stoddart, as a ‘great theatre of a new and more impressive class of natural beauties’. Almost overnight, Scotland became a land of mist and magic. How did this happen?

This process of mythologising began in the late 18th century, with the impact of James MacPherson’s ‘translation’ of Ossian: Fragments of Ancient Poetry (1760). A public growing weary with the dry rationalism of Enlightenment were taken by these 'otherworldly' folk tales of poetic melancholy and the notion of the 'noble savage' from a magical land far away on the northern fringes of civilised Europe. MacPherson's work has been well-documented in its instrumental role in bringing forward the association of the Highlands as a visualisation of the sublime, but few could have predicted the permanent hold this would assert upon the collective imagination.

This 'imagined Scotland' is an image that was later projected on to the world stage through the international success of the novels of Walter Scott and his depiction of idealised Scottish heroes and dramatic landscapes. The ‘exotic’ Highland culture was soon appropriated by Lowland Scotland and became the iconography of a nation. By the late 19th century, a fashion for all things tartan prompted those who could afford it – Britain’s nobility and elite - to emulate their Queen in buying sporting estates. What followed was the process of ‘Balmoralisation’ of Scotland (a reference of course to the purchase of Balmoral as Queen Victoria’s summer residence in 1848). Balmorality was particularly significant because it was accompanied by a very selective and incomplete narrative, a narrative that was perpetuated by writers and visual artists of the time. Edward Landseer was perhaps primary among them, building a reputation on the depiction of the familiar stags, glens, kilts. Symbolic of this era is the iconic image, Landseer’s ‘Monarch of the Glen’ (1851):

Wild Land?

“The bald unpalatable fact is emphasized that the Highlands and Islands are largely a devastated terrain, and that any policy which ignores this fact cannot hope to achieve rehabilitation.”

— Frank Fraser Darling, West Highland Survey: An Essay in Human Ecology

Potent cultural imaginings can quickly become ‘realities’ that can affect local practices and politics. For example, there is a very current discourse around ‘wildness’ or ‘wilderness’ in Scotland. Wildness, like ‘nature’ itself, is a discourse, laden with bias, expectations and values. Some would argue that ‘wildness’ and the meanings ascribed to it is a post-Enlightenment industrial era fantasy, a place that exists in the Western imagination – a retreat we have created to escape the advances of modernity.

In the following quote, historian James Hunter James Hunter gets straight to the point: ‘The average Highland glen is about as natural as a motorway embankment.’ This is provocative, certainly. As any ecologist worth their salt will tell you: There is no Wild Land in Scotland. What we often take to be ‘wild land’ is really a closely managed political ecology that has turned these landscapes of privilege into the familiar canon of Scottish ‘scenery.’ As a consequence, much of the Highlands are maintained in a state of near desert, solely to support the recreational bloodsports of princes and bankers. What is being ‘protected’ is not just the ‘appearance’ of specific landscapes, but a wider aesthetic, a vision of what Scotland’s landscapes should look like – that ultimately has its provenance in an eilte way of seeing.

The following quote is from Lord Vat of Glenlivet, a fictional character from the famous play The Cheviot, the Stag and Black Black Oil. I'll come back to this play later.

“Get off my land! These are my mountains! ...Look here, I’ve spent an awful lot of money to keep this place private and peaceful. I don’t want hordes of common people trampling all over the heather, disturbing the birds.”

This is not a matter of history being covered over by forgery, but a case of one specific history replacing another. The key point here is that such a version and vision of Highland history denied its people any contemporary political agency. In historical terms, this ‘imagined’ Scotland appeared at the same moment that saw industrialisation and modernity. In a time of unprecedented change across rural Britain, nowhere more so than the north of Scotland, the Highlands were perceived by the world as ‘timeless’ and ‘unchanging.’ From 1760 to 1860 the population of lowland industrial capital of Glasgow expanded from just over 80,000 people to half a million, and brought with it a social and health maelstrom. Glasgow of 1885 was called the ‘Scottish Chicago,’ for its sprawling urban concrete and steel expanse, underground railways, overcrowding and booming leisure industries. In reality, the Highland region became a source of military might for the British Empire - a huge, untapped grazing ground for the growing sheep-rearing industry with thousands cleared from their land, and a killing-field for elite sportsman. A whole culture was decimated and its material artefacts became the markers of a new British elite’s privilege.

“All the treacheries and sordidness of the clan life and of Scottish history were forgotten; a tartan patchwork quilt was laid over these, for the industrial age was here, an age that considered history as something utterly dead, of use simply as a tickler to replace genuine sentiments that had been jettisoned from life as unpractical or indecent.”

— George Scott-Moncrieff, 'Balmorality' in David Thomaon (ed), Scotland in Quest of Her Youth (1932).

Due to the fact that Scotland has not had (at least until recently) a developed film industry, representations of the landscapes from outside - often through a British or Hollywood lens - have prevailed in people’s minds. It is a well-known story that by the 20th century, during the 1950s, Hollywood producer Arthur Freed went to Scotland to search for locations for the shooting of his all-singing-all-dancing feature, Brigadoon. He visited the most representative and picturesque sites of the land, but was not convinced of the ‘Scottishness’ of these places. Famously, he decried, “I went to Scotland, but I could find nothing that looked like Scotland.” As his words reveal, the filmmaker was not looking for Scotland itself, but for something that resembled what he wanted Scotland to look like: a dream world of pre-industrial villages folk customs and bagpipes. In the end, he decided to shoot the film in a Hollywood studio, where his imagined Scotland could be ‘faithfully’ recreated. As was to be expected, the result was a film which offered a highly romanticised representation of Scotland far removed from reality. Every 100 years, the people of Brigadoon awaken for a 24 hour period and then go back to sleep for another century, while Brigadoon itself vanishes in the mists. The film is quite sweet, but interrogating the cultural politics of how it came to be reveals a far more interesting - and important - story.

Such cultural tropes have monopolised the creative and political field of cultural production in Scotland for many years and it is still the case that Scottish artists, film-makers and writers struggle to gain international attention if they fail to indulge in the romantic image (of course, with a few notable exceptions). The most internationally recognisable image of Scottish culture in recent years is, of course, Outlander. More of that later.

Tourism: Scotland the Brand

Such a 'way of seeing' also helped to initiate a global industry of tourism. Scotland pretty much gifted tourism to the world; many countries could only dream of the cultural brand Scotland has. Given that we don’t have great weather, tourism is based on two things: history and scenery. Of course, in selling the past, certain histories dominate while others are suppressed. Are we really happy to reduce the Highlands to a cross between a national park and an open air folk museum?

We had 'Balmoralisation' in the 19th century, and now I’m coining a new word – 'Outlanderisation' (hoping this might catch on...). I mentioned Outlander earlier. I have several opinions on Outlander, and they are not all bad! As a huge positive, Outlander inspires people to learn more about the place, language and culture, and to be fair to producers and researchers - unlike the 1950s - a lot of research has gone into sourcing authentic Gaelic material. The question remains, why do we need to exploit a fictional story when there are so many other forgotten stories we could draw upon? And not just forgotten stories, but a dynamic, living culture? Alongside Outlander, we have an orchestrated marketing campaign led by state-supported VisitScotland. Tourism creates jobs; it generates profit. At what cost? There are several immediate problems. When it comes to the discourse surrounding 'cultural tourism,' the phrase ‘community development’ as used by local government is a word that commercial interests have made virtually synonymous with ‘sustained economic growth.’ This is a fallacy, based on a model of competition rather than mutual co-operation. We need to change the framing here. Community development should be about creating the conditions and enabling communities of place to flourish, not to exploit themselves for commercial gain by competing with the next village up the road for coffee stops and claims to Outlander authenticity.

We need to challenge the dominant touristic and nationalistic narratives that essentially serve the bureaucratic elite. We need to re-member, re-vision and re-claim.

Cultural Renewal

Let’s get to get back to this idea of re-connecting with the land. In a series of essays on ‘cultural renewal,’ writer Kenneth White calls for need to ‘reground’ - to re-connect country with ground. ‘A country begins with a ground, a geology,' he writes.

“When it loses contact with that, it’s no longer a country at all. It’s just a supermarket, Disneyland or a madhouse.”

— Kenneth White. The Wander and his Charts: Essays on Cultural Renewal (2004)

Let’s take some time to unpick this quote.

A Supermarket. This is global capitalism writ large, where everything is a commodity to be bought and sold. Everything (and everyone and everywhere) becomes disposable, seen simply in terms of resources at hand, ready for exploitation, for profit. Capitalism does not require or want active citizens: it wants active consumers. The most effective consumers in a capitalist society are unhappy, unhealthy, lonely individuals with no real relationship with each other or with their place. This is true whether you live in a high-rise block in an urban centre or in the rural Highlands.

Disneyland. A stereotyped culture staged for tourists. This affects the public’s ability to not only know the story of their own place – through no fault of their own – but also their ability to imagine alternatives. In the 1970s, writer Tom Nairn famously proclaimed the vast presence in Scotland and abroad of ‘tartanry’ – shorthand for the kitsch shortbread image and garish set of symbols – as the ‘tartan monster.’ The argument in Scotland was that because national identity could not take a political form of expression, it was subverted into a cultural backwater of deformed nationalism. A number of writers have argued that this so-called monster has distorted Scottish culture giving rise to the opinion that Scotland is too provincial to be aligned with modern modes of political and cultural progress. When a generation of young people define themselves solely by such empty superficial stereotypes that bear no relation to their own lives, relationships or communities, how can we expect them to take themselves seriously as local and global citizens?

A Madhouse. Perhaps not the most politically correct term, but I interpret this as a breeding ground for the kind of right-wing populism and divisive polarisation we see increasingly all around. We see this manifest in the headlines of our daily politics, the politics of isolationism (#Brexit) and a retreat into ethnic nationalisms. Trump. Farage. In a society that has lost contact with ground, with the land, the question of national identity becomes paramount, obsessed with questions of who ‘belongs’ and who does not. This is the mask of a deep set alienation - from ourselves, our communities and our environment.

These are the immense questions of our times, reaching far beyond us here in the Scottish Highlands. In many ways, Highlands are a lived microcosm of tensions arising across the globe.

The importance of Gaelic

I’d like to discuss here the importance of Gaelic. In my view, Gaelic activism is vital to land activism in the Highlands. Others might see things differently; some might even feel quite alienated from this argument. This topic is discussed in this book, On the Other Side of Sorrow: People and Nature in the Scottish Highlands (2014 - first published 1995). The question is, at what point do arguments for cultural loss become exclusivist, as distinct from being critiques of unequal power relationships? This is the nub of it. We cannot fan the flames of right-wing populism and divisive polarisation with questions of who ‘belongs’ and who does not. If people and place are ever to achieve sustainability, we need minds that that can draw the ‘significant lines together’ through history and culture to push culture forwards, developed with, not against, the past – not out of romantic hankering for paradise lost, but from an acute sense of ecological and human responsibility.

In Gaelic culture, there is the notion of dùthchas – which takes in both a sense of place and belonging, linked to the land itself, and a responsibility to the ‘stewardship’ of that land - dùthaich - rather than 'ownership.' Dùthchas is also connected to our cultural inheritance - our cultural or collective memory - our dualchas. These words are all connected; together they form a matrix in which land and culture are inseparable. If we are talking about policy on land reform in the Highlands, it is surely vital that we look at the big questions through this cultural lens. If you are interested in the Gaelic perspective and worldview, I would recommend the following book: Dùthchas nan Gàidheal: Collected Essays of John MacInnes (2010), edited by Michael Newton.

Globally, the call for ‘culture’ is becoming ever more powerful along with the increasing ecological, economic and social challenges to meet the aims of sustainability. The UNESCO Hangzhou Declaration in 2013 puts culture at the very heart of ‘sustainable development.’ This very much includes approaches to safeguarding and facilitating engagement with intangible cultural heritage:

“Culture is precisely what enables sustainability – as a source of strength, of values and social cohesion, self esteem and participation. Culture is our most powerful force for creativity and renewal.”

— UNESCO

UNESCO state that cultural and biological diversity are intimately related and ‘equally significant and important for sustainable development.’ Yet there is not the general consciousness that cultural diversity is under threat world-wide in the same way that there is now a general awareness of the threat to biodiversity. It might be easier for us to grasp the need to protect a rare bird species, for example, but not so easy to grasp or understand the value of a rare Gaelic song. Both are rare, precious and unique on the planet. Myths, stories, songs and poetry contribute to global cultural diversity as creative expressions of our relationship with local places. Together they form a cultural ecology which encodes and passes on knowledge of local flora and fauna and their uses, seasonal changes, geological forms. If we allow languages and cultures to die, we directly reduce the sum of our knowledge about the land.

In his essay ‘Real People in a Real Place’ (1982), poet Iain Crichton Smith denounced what he called historical ‘interior colonisation’ along with a growing materialism which he believed had left Gaels in a cultural milieu increasingly ‘empty and without substance.’ As writer Iain MacKinnon has noted, such a view resonates with perspectives on colonisation now being made by writers and scholars of indigenous peoples peoples across the globe. Such perspectives describe symptoms of human-ecological disconnect, alienation and loss of meaning – an indicator of just how far our human psyche and culture has become divorced from our natural environments. Addressing this problem requires the collective work of decolonisation. Cultural renewal takes us forward, it doesn't re-perform the past. Framed this way, it becomes an ecological imperative to recover meaning, to recover context.

James Hunter asks us to imagine a way into the future when the Highlands have been put right, ecologically, socially and culturally – restoring life and community. This doesn’t require everyone to learn and speak Gaelic. It does, however, require everyone to recognise, respect and understand the culture of this place. Can we get to a place where person’s ancestry becomes of much less importance than the fact that such a person lives in, works in, is committed to a place? In order to do this, we need a culture of deep listening and dialogue - of interpretation, translation and respect:

“A person belongs inasmuch as they are willing to cherish and be cherished by a place and its peoples.”

— Alastair McIntosh, Soil and Soul: People v Corporate Power (2001)

Shaping Our Stories

Writer and cultural activist Arlene Goldbard, from the USA has a very simple message: how we shape our stories shapes our lives.

Individual lives are shaped by the stories we tell. If I lose my job, do I see it as a personal punishment that shames me, or do I see it as a common story, affected by larger socio-economic forces, and therefore a personal spur to collective action? One of these stories sends me into despair, the other into possibility.

Goldbard writes that 'art is the crucible in which we forge identity, community, shared values, and a sustainable future.' The capacities that can be best learned through art, she writes, can be used to transform our collective story to one of possibility: social imagination, empathy, improvisation, awareness of cultural citizenship, resilience, connectivity and creativity.

Bringing about change and transformation requires us to re-shape our stories. As it is for individuals, so it is for groups, communities, societies. In every society there is a dominant story. These stories are both real and imagined, comprising fragmented histories and many layers of narrative, but the story, like our own identity, is always fluid and evolving. We can choose despair, or we can choose possibility. We need a new generative mythology, one that supports life and community.

Many people, perhaps of a certain generation, subscribe to the old order's assertions of its rightness and permanence, leaving them afraid to imagine new possibilities (let alone get their hopes up). They are stuck in the mindset of demoralising orthodoxies (most likely a direct correlate to the amount of mainstream news media they consume). Unfortunately, these people often mistake being demoralised for being ‘pragmatic’ or simply 'realistic.' We've all met these characters - those for whom the answer is always 'no, can't be done' before it is 'yes' (or even close to a 'maybe?'). Now, more than ever, we need to see through the facade of so-called ‘reality’ into a new universe of possibilities that we have the power to shape.

Think back on how powerful acts of storytelling can be. Music and theatre, as expressive forms, can bring people together in conviviality, creating a space to rehearse and perform alternative realities. A great example is The Cheviot, Stag and Black Black Oil, mentioned earlier - written by John McGrath in the 1970s and toured by theatre company 7:84 . This play captured the collective imagination, reflecting back to communities, often for the first, time, their own history and culture. The play is widely heralded recognised as a hugely important cultural moment, and a tipping point - the moment that connects the radical roots of land story in Scotland to the modern story of community land.

“At surface level, it is a question of politics. At a deeper level, it’s a question of poetics…If you get politics and poetics coming together, you can begin to think that you’ve got something like a live, lasting culture.”

— Kenneth White

Poetics (literally: ‘the making') in this context, goes beyond the literary form of poetry to take in both music and song and other, deeper forms of creativity. 'Arts and culture' are not something artists do over there in a policy box, separate from the rest of us. Heritage is not a fixed set of objects and practices from the past that need to be re-performed in the present. Heritage is not separate from culture. 'Culture,' in the collective sense, begins with a group of individuals - whether group, community or nation - and ‘art’ is the creative expression and manifestation of that culture in an ongoing process, re-shaped by each generation in new and meaningful forms.

Rather than drawing on the creativity of ‘the artist,’ as someone else, there is a sense too in which we must become artists ourselves. This does not mean that we should all pick up a paintbrush; rather, this is the idea that we all have the power to transform and be transformed in a constant creative process. This is what underpins the idea of creative activism, something we will talk about in workshops later.

All of us enlarge possibility by understanding our role as culture-makers. As active citizens. To underpin lasting change, we need artists and other creators of culture who can elicit and link many different stories into those that create possibility rather than foreclose it.

The Future / àm ri teachd

I started by painting a bleak picture. I’ll finish on a positive, because there are hugely positive stories to tell. We can see glimpses of the future right here in the present. In very recent times, we have all felt that cultural energy, witnessed a blossoming of cultural confidence and consciousness. There is evidence of a live, lasting culture all around, and increasingly so.

My generation, those of us born in the 1980s - those of us who were wee in the 90s - have lived through a time of huge transformational shift. We now see a generation more culturally confident than we have ever been. The 1980s saw the introduction of Gaelic medium education the the seeds of the Fèisean education movement, which, in the Highlands, began the process of ‘re-connecting people to their cultures, their music and their untold stories.’ In the 1990s we saw a wave of land reform – Assynt, Eigg, Gigha. In 1992, following the Rio Earth Summit, environment and sustainability crept into policy and legislation. We saw Devolution & the new Scottish Parliament. The internet happened. In the context of the land debates, the first Land Reform (Scotland) Act was passed in 2003. A new Scottish Government came in 2007 and we saw the Scottish independence referendum of 2014. The referendum left a legacy of cultural confidence that has fed into an emerging sense of cultural possibility, catalysing artists, activists and citizens into a large scale participatory democratic process and opening up new grassroots spaces (the Architecture Fringe emerged out of this context). Since 2014 we have seen more land reform, driven by the grassroots, with the second Land Reform (Scotland) Act in 2016.

The story of community land ownership, to me, is an incredibly exciting one. It is a potent and powerful story, one of diversity, resilience, a story with radical roots and looking out to the future. It challenges the established order and grand narratives. It’s a story of how people can work together to overcome seemingly impossible barriers. Community land is a culture of possibility. Each story is a microcosm of change, transformation and self-determination – ‘independence from within’ - opening up channels for others to follow. Those of you involved in this movement can see the emergent reality – the larger narrative. I'll leave you with these two quotes:

“Community land will become the story of the 21st century: the unleashing of a new sense of confidence, energy and opportunity”

— James Hunter, From the Low Tide of the Sea to the Highest Mountain Tops: Community Ownership of land in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland (2012)

At the same time, it’s vital to remember that:

“Not everything will get fixed in your own lifetime, no matter how hard you try. It’s a long game...But we’ve seen more progress in our own lifetimes than we would have dared hope for.”

— Issie MacPhail, Assynt Crofters, 2018